Link to the scientific articles:

Vegetti, F. (2019). The Political Nature of Ideological Polarization: The Case of Hungary. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), 78–96.

Vegetti, F., & Širinić, D. (2019). Left–Right Categorization and Perceptions of Party Ideologies. Political Behavior, 41(1), 257–280.

Perception and the political space

In the political science jargon as much as in everyday language, the preferences of political actors are usually referred to as their “position”. When we speak of “the Lega’s position on immigration”, for instance, we refer to the ensemble of policies that the League proposes for managing immigration. Implicit in the idea of “position” is reference to the idea of “space”, which allows for an intuitive, albeit abstract, representation of the similarities and differences between political actors. Two parties which propose very different policies will be perceived as “distant” (as are e.g. the Democratic Party and Brothers of Italy), while parties which are similar will be perceived as “close” to each other (as are e.g. the Lega and Forza Italia).

In most Western democracies, the relative positions of parties and voters are represented – by scholars as well as by the media and by political actors themselves – as aligned along a left-right axis. When citizens vote for a party because they perceive it to be closest to their own position in the left-right space, it is customary to say that they vote ideologically. That is to say, citizens are presumed to support the party which they perceive as closest to their own stance – regardless of other aspects such as the competence of candidates or the probability that the party will get any seats. Since many people actually vote on the basis of this very perception, it is crucial to understand how the perception is formed and what non-random factors are capable of influencing it.

Party strategy and perception

The perception of a party’s political position can be systematically skewed with respect to the actual content of its electoral programme. This issue is at the core of two articles by Federico Vegetti, both as a single author and as a co-author together with Daniela Širinić.

In his analysis of electoral behaviour in Hungary (Vegetti, 2019), Vegetti shows how the huge ideological differences between right-wing parties (including Fidesz, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s party) and left-wing parties, as they are perceived by Hungarian voters, do not match the equally great differences in those parties’ electoral programmes. The perceived level of polarization in Hungary is unmatched by any other European country, and is far greater than one could infer from the analysis of election manifestos alone. According to Vegetti, the cause of this skew is to be found in the kind of information that voters have as well as in party strategy. When citizens assess a party’s ideological position, they do not only take into account its politics, but also its strategy with respect to coalition-building: parties that form alliances before or after the elections are perceived to be more similar to each other than they would appear on the basis of their respective electoral programs.

From 1990 – when the first post-Soviet election was held – through to 2018, no government coalition in Hungary included both left-wing and right-wing parties. The absence of left-right coalitions in Hungary’s recent political history has contributed to increasing the perceived homogeneity between parties within the same ideological camp, while amplifying the perceived difference between parties belonging to opposing ideological camps.

This skew has been further strengthened by the mutual delegitimization of parties from opposing camps, as well as by a predominantly majoritarian voting system. This spurs competition based on emphasizing the opponent’s alleged but catastrophic unfitness to rule. As a result, voters perceive left-wing and right-wing parties as radically incompatible, and their ideological positions as more radically distant than they actually are.

The role of categorization

The study of the Hungarian case establishes a relation between parties’ strategies and the citizens’ perception of those parties’ position on the left-right axis. However, it does not investigate the cognitive mechanisms that translate the information that parties provide into individual perception. In another study, Vegetti and Širinić (2019) suggest that categorization plays a central role in this. Categorization is the process by which the human mind groups and differentiates objects – whether physical or abstract – on the basis of their belonging to pre-established categories.

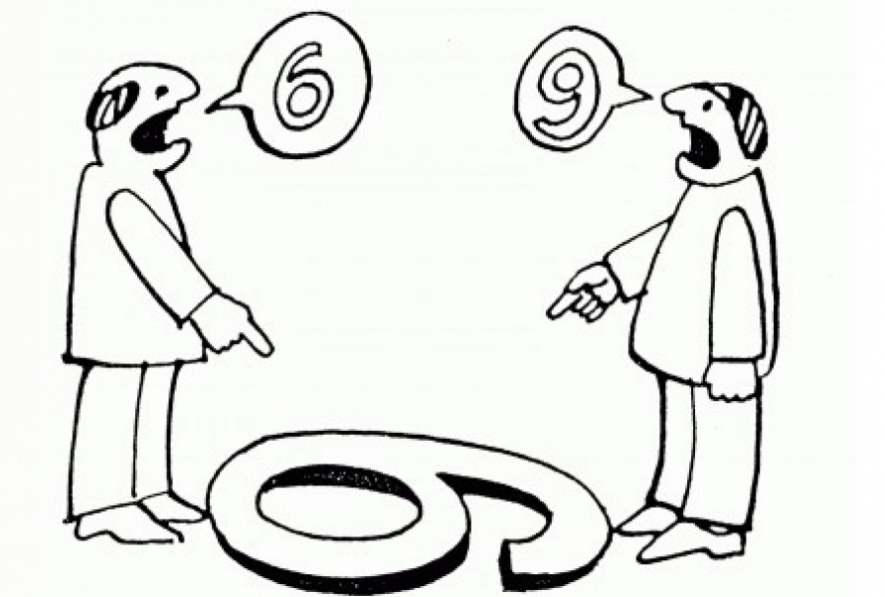

Categorization helps us in two ways: it allows us not to get confused between different objects, and it allows us to save cognitive resources when we are faced with an object that belongs to a known category. For example, categorization allows us to recognize an apple as “an apple” at a glance, without evaluating each characteristic in detail, and at the same time it allows us to distinguish an apple from an orange. However, in order to save cognitive energies categorization skews perception in a peculiar way: objects that are known to belong to the same category are perceived as more similar to one other than they really are, and those that are known to belong to different categories are perceived as more different.

In political communication, “the left wing” and “the right wing” do not only refer to parts in the political space in which to situate a political position. In many countries, they also refer to existing groups of actors, be they parties or citizens. When this happens, “the left wing” and “the right wing” work like full-fledged categories in the above sense. While political positions are aligned along a continuum, and therefore allow for more nuanced variants (there can be far-right policies and right-of-centre policies), categories are univocal and mutually exclusive (being from the left wing automatically excludes being from the right wing). Which of the two meanings is intended when the terms “the left wing” and “the right wing” are employed depends on the context.

In such countries as Hungary and Italy, for example, “left-wing” and “right-wing” have strong “group” undertones and are often considered to be mutually exclusive categories. In other countries (typically Northern European ones), the “categorical” component leaves room to the positioning of policies along the ideological spectrum. Vegetti and Širinić’s empirical analysis shows how the perceived polarization is greater where “left-wing” and “right-wing” are more often presented as exclusive categories, and how citizens tend to perceive parties from a different political camp than their own as ideologically more distant from them than they actually are. The two studies show how citizens’ perceptions are more influenced by the rhetorical style that parties use to campaign against one other than they are by those parties’ politics.

More specifically, when politics appears to be a conflict between mutually incompatible groups, citizens acknowledge the fact that those groups’ ideological position are incompatible with one other, even if this is not necessarily true.